David as Mr. Pumpkinhead at Santa’s Village, Summer 1963

David at University of Cambridge, 1968

Marianne and David Richards, July 2014

David and former President Clinton, Yale Law School, 2014

“This experience led to his prize-winning senior thesis on air rights, and this expertise figured into (1) the sale of the Tiffany’s store air rights to Donald Trump for Trump Tower in 1984, and (2) the shaping of legislation from 1999 to 2006 using air rights to preserve the elevated railroad viaduct the High Line”

David and Kim Cattrall, 2007, at PBS program on My Boy Jack, and Kipling’s son’s WW One death

“In 2010, he was the featured real estate lawyer in that year’s issue of New York Super Lawyers”

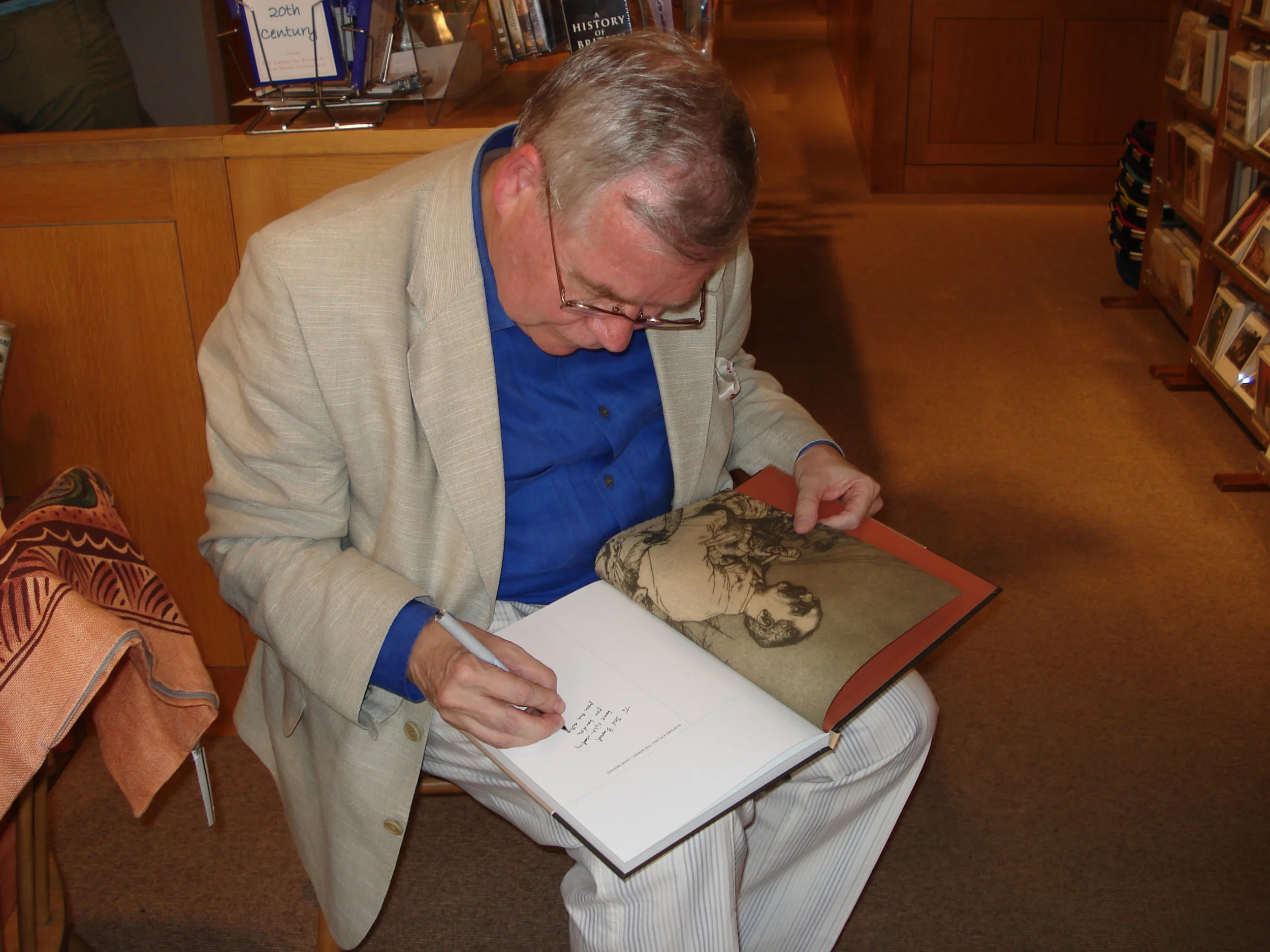

Signing copies of "Kipling: The Books I Leave Behind" at the Beinecke Rare Book Library, June 2007

THE AUTHOR

David Alan Richards was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1945, the first of three children of Charles and Betty Richards. His father learned of David’s birth when handed a note from another Navy flight crew in the Pacific, where World War II was just ending. When David was twelve, the family moved to San Bernardino, California, for his father to begin working at Norton Air Force Base on the then top-secret Lockheed reconnaissance aircraft the SR-71 Blackbird.

The influx of military and civilian families to that Southern California city made David’s Pacific High School the largest in California, as evidenced by his graduating class size of 1,100. His first summer job was as Jack Pumpkinhead at Santa’s Village in 1962, though this did not prevent him from being admitted to Yale University the following year.

Arriving in New Haven was something of a culture shock— one of his first roommates was named Cornelius Searle Vanderbilt Whitney— but he acclimated, and majored in American Studies. He graduated summa cum laude while working as a research assistant to an English literature professor and next to an American history professor, as well as being a student campus guide. In the spring of his junior year, he was tapped for the senior, secret society Skull and Bones, sandwiched between society delegations which included John Kerry above and George W. Bush below.

“By the time he graduated in June 1967, he had won the most prizes in his class, in English literature, American history, book collecting, and speech”

Speech awards comprised best orations in both the junior class, on marching at Selma, Alabama, in 1965—his prize presented by the previous winner, John Kerry—and senior class, which Kerry had not won, on opposition to the Vietnam War (after which David’s father ceased all communication with him for six months out of anger). David also captained his residential college debate team to inter-college victory, and was a member of the University debating team.

David was named by the Yale administration to the Senior Advisory Council, where he served as chair of the Student Committee on Teaching, succeeding in a campaign to change Yale’s grading system. His prize-winning senior thesis on a Puritan woman’s narrative of Indian captivity has been repeatedly cited by subsequent historians, most recently Jill LePore’s The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origin of American Identity (1999) and Stacy Schiff’s Witches (2016).

In the summers of 1966 and 1967, David lived in the New York Yacht Club, then the home of the America’s cup, and researched the Club’s social history. The result was a 1974 two-volume history entitled The History of the New York Yacht Club. This had an unexpected benefit his senior year. When David was nominated for one of the five annual Keasbey Fellowships to Oxford and Cambridge, his interviewers included two with forebears in the NYYC. In the fall of 1967, five Keasbey Scholars, including David, joined 32 Rhodes Scholars to sail to England on the S.S. United States.

At Cambridge, David entered Selwyn College, a mid-Victorian college so small, there were no Modern History fellows available to tutor him. Farmed out to dons (professors) in other colleges, he was fortunately assigned to among others Norman Stone, then a young don in Gonville & Caius College. Decades later Stone was appointed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as the Regius Professor of History at Oxford, and was one of the models for the TV-talking-head university professors in Alan Bennett’s play and movie The History Boys.

Stone (in Cambridge vernacular) “coached” David for his final, three-day exams to a First Class B.A. degree, ranking second in scores among the students in the History Faculty, and surprising those at Selwyn College, more renowned for rowing regattas than scholarly pursuits. It was then David first encountered the histories of the British Raj and World War I, to bear fruit three decades later when he began assembling first editions and manuscripts of Rudyard Kipling, born in India, and losing a son (without ever finding his body) in that war.

“David received his M.A. degree from Cambridge in 1971.”

He returned from Cambridge to Yale Law School, having declined acceptance to Harvard’s Law School as he needed employment to pay for his continuing education, on offer only in New Haven. His first assignment, in the summer of 1969, was at the direction of then Yale University President Kingman Brewster: to author a history of the Yale Corporation from the university’s founding in 1701 to date. The aim was to explore how the Yale board’s membership might be expanded to include more than exclusively white Protestant males. David determined that a change in the Yale charter in the 1870’s might be interpreted to have freed candidates for Corporation membership from any restrictions as to gender, race, or religion, and persuaded the University’s law firm to write an opinion letter to that effect based on his research. Within two years, the first two women were added to the Yale Corporation, and other non-WASPS soon followed.

Another benefit of working for the Yale administration came in June 1969, when David met his future wife, Marianne Del Monaco. She was working for President Brewster as one of his three office secretaries, and was the beautiful one front and center. While Marianne was initially underwhelmed by David’s faint English accent, Beatle haircut, and guardsman’s mustache, they were married in the spring of 1971.

A condition of David’s university job was his reluctant agreement to forgo competing for a spot on the Yale Law Journal, the customary gateway to a Federal judicial clerkship and big-law-firm employment. Instead, David was the only member of the Law School class of 1972 (where one of his classmates was Hillary Clinton, Bill being in the class behind them) to be awarded two essay prizes by the Law School. His senior thesis on a New York City zoning technique known as development rights transfer caught the attention of Yale Law Journal editor-in chief Richard Blumenthal (later the U.S. Senator from Connecticut), who asked permission to publish it in the Journal, which David happily gave.

David’s first job as a certified (but not yet licensed) lawyer was as a summer clerk in 1971, with the New York City firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, and Garrison. At that time, their real estate department represented the Penn Central Railroad, then in bankruptcy, in the sale of the railroad’s NYC hotels. David drafted the firm’s legal opinion letter on the sale of the Grand Central Terminal development (air) rights, which could be bought in conjunction with one of the hotels. This experience led to his prize-winning senior thesis on air rights, and this expertise figured into (1) the sale of the Tiffany’s store air rights to Donald Trump for Trump Tower in 1984, and (2) the shaping of legislation from 1999 to 2006 using air rights to preserve the elevated railroad viaduct the High Line, the public park on New York City’s West Side, now the city’s most popular tourist attraction.

David moved in 1977 to Coudert Brothers, as that international law firm’s first real estate lawyer. There he became a nationally recognized expert in foreign investment in the United States, and was that subject matter expert for the American Bar Association and the Practicing Law Institute. He also shared traveled extensively giving speeches throughout the United Kingdom, Canada, Hong Kong, Switzerland, West Germany, and the Netherlands Antilles.

He left Coudert as a partner in 1982 to co-found the New York City office of Sidley & Austin, then the largest law firm in the United States. In 1999, he was de-equitized with 29 other partners over the age of 55 when Sidley attempted to adjust its “profits-per-partner” status by simply reducing the number of partners.

David was the only one of the de-equitized partners who permitted himself to be publicly identified as such in The American Lawyer, the Chicago Tribune, and other newspapers, and on National Public Radio.

After the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in Chicago alleged age discrimination by on behalf of that class of individuals, for which David was the primary witness, the case was settled with payment of millions of dollars divided among the dismissed partners.

Meanwhile, David became a partner with the New York office of McCarter & English, and was its managing partner from 2000 to 2005. He left McCarter in 2013 to become Senior Counsel in the New York office of Steptoe & Johnson LLP, an international law firm headquartered in Washington, D.C., where he continues to practice real estate law part-time. In 2010, he was the featured real estate lawyer in that year’s issue of New York Super Lawyers, under the title “Manhattan Transfer.”

During his law firm career of over forty years, David was active in national and international bar associations. He became the youngest chair of the 35,000-member Section of Real Property Law in the American Bar Association in 1990-1991, and the youngest chair of the 100-member Anglo-American Real Property Institute in 1991-1992, while serving on the board of the American College of Real Estate Lawyers. In 2003, the American Bar Association published a book he co-edited, The Commercial Office Lease Handbook, a comprehensive overview of New York leasing law.

His professional career was not without its reverses, however. In the real estate industry meltdown of 1989, when his real estate firm group at Sidley & Austin shrank from nine lawyers to three, and David internalized it was somehow his fault, he suffered from clinical depression and was hospitalized. Fortunately, while in treatment, his doctor urged him to resume a pastime that once brought him joy. Recalling his Yale College book-collecting prize, he started (with more disposable cash than as a collegian) collecting rare books. He first collected the World War One poets Sassoon, Graves, and Owen, and then—combining David’s interests in the Raj and World War One—expanding to Rudyard Kipling.

“In a dozen years, purchasing from Ebay, bookdealers, and at auctions in the U.S. and abroad, he amassed the largest collection ever of Rudyard Kipling works including several “only known copies.”

All 2,500 items were gifted to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (to which, as a Yale student tour guide from 1963 to 1967, he led university visitors). The full-building exhibition of his collection at the Beinecke in 2007 was the occasion of his writing the Yale University Press-published catalogue, Rudyard Kipling: The Books I Leave Behind.

Three years later, based on examination of his personal collection and other Kipling collections in the U.S., Canada, Great Britain, and South Africa, he published Rudyard Kipling: A Bibliography, now the premier source cited by scholars and auction houses Sothebys and Christies, the subject of David’s Bernard Breslauer memorial address on bibliography in 2009, and nominated for Best Bibliography by the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers in 2011. Over the years he has written several other scholarly articles on Kipling, both published in the Kipling Journal and archived on the Kipling Society’s website.

In 2000, David was elected to the board of the Russell Trust Association, the corporate parent of the Yale senior/secret society Skull and Bones. Realizing that, unlike the five other Yale secret societies with “tombs,” his society had never had an official published history— and that no serious scholarly history of the society system existed—with the permission of his board (assured he would print nothing not already published elsewhere), he embarked on the writing of Skulls and Keys: The Hidden History of Yale’s Secret Societies.

His other corporate board service included being former secretary of the Grolier Club, America’s oldest and largest rare book collecting society; former secretary of St. Bart’s Conservancy, formed for the architectural preservation of St. Bartholomew’s Church on New York’s Park Avenue; and in July 2021 he became president of Great Britain’s Kipling Society, the first non-Briton to have that post since the Society was founded in 1927. Also a member of New York City’s Yale Club and Union Club, David serves in New Haven, CT at his Alma Mater as President of the Yale Library Associates, as a member of the University Librarian’s Council, as an Associate Fellow of Davenport College, and as a Sterling Fellow.

In 2021, his latest book, I Give These Books: The History of the Yale University Library, 1656-2016, was published by Oak Knoll Press.

David and Marianne moved from New York City to Scarsdale, New York in 1977, where they raised two children, Christopher and Courtney. In 2017, the couple moved to Stamford, Connecticut, to be nearer to their three grandchildren.